The living skin of the rangelands

Creating farm carbon accounts has been an important part of the four-year Rangelands Living Skin project, helping participants establish a baseline from which to identify and embrace opportunities for farm greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions improvements.

The Rangelands Living Skin (RLS) project kicked off in 2021 with a core group of four producer families and a team of scientists and other collaborators.

Together they are evaluating cost-effective practices – chosen by the producers – that focus on regenerating the NSW Rangelands to support production now and into the future.

Rotational grazing, ponding, ripping, multi-species plantings and biological soil amendments are just some of the management practices being trialled.

The project aims to create an evidence base for encouraging widespread adoption of practices that benefit soil, plants, animals and people – the living skin of the rangelands. The project is funded by Meat & Livestock Australia and led by the NSW Department of Primary Industries.

The four core producers involved in the project are:

- Andrew and Megan Mosely, ‘Etiwanda’, Cobar NSW

- Gus and Kelly Whyte, ‘Wyndham Station’ and ‘Willow Point’, Wentworth NSW

- Graham and Kathy Finlayson, ‘Bokhara Plains’, Brewarrina NSW

- Glenn Humbert and Julie Conder, ‘Gurrawarra’, Bourke NSW.

Meet the producers – the Mosely family

Mixed livestock producers, Andrew and Megan Mosely Andrew and Megan Mosely run White Dorper sheep, semi-managed Rangeland goats and Red Angus cattle on Etiwanda. When they took over the property in 1997 it was a wool operation facing significant challenges, including degradation in the landscape through capped soils and invasive native scrub, which was inhibiting the growth of grass and profitability of the business. They undertook Holistic Management training in the 90s and began fencing to get control over grazing and rest periods. As a result of their intensive rotational grazing practices and subsequent improvements in land condition, Andrew and Megan are currently able to run twice as many domestic livestock than prior to their management change, and to the regional average. The Moselys currently run 10,000–20,000 DSE, depending on the season. They note this is partly due to extra grass growth from the last few years of good rain, but largely due to their grazing management and the combination of enterprise types working together. As part of the RLS project, the Moselys are trialling plantings of multispecies pastures and annual legumes. They are also trialling biostimulants, as part of replicated plot trials across all four participants’ farms. |

Meet the producers – the Whyte family

Sheep and cattle producers Angus and Kelly Whyte Attending a Resource Consulting Services (RCS) Grazing for Profit course in 2001 was a turning point for Angus and Kelly Whyte, who run a sheep and cattle breeding and trading enterprise on Wyndham Station and Willow Point. Two decades ago, they were frustrated with the increasing amount of work they were doing at Wyndham Station and the increasing degradation of the landscape. “The low-level set stock management regime in our part of the world just seemed to be taking our landscape backwards and creating more work,” Angus said. Following the Grazing for Profit course they began creating smaller paddocks to facilitate rotational grazing and to match stocking rate to carrying capacity. By changing to rotational grazing, moving the animals has become less labour-intensive, and there has been greater plant growth and diversity, as well as reduced erosion. While they continue to manage holistically to drive productivity, profitability and landscape health, the Whytes are also interested in the potential co-benefits of ecosystem services markets. These emerging markets, such as soil carbon and biodiversity, offer the potential to better compensate producers for the work they are doing to improve the landscape. As part of the RLS project, the Whytes have undertaken a water ponding trial, rehydrating a 300ha clay plan area on Willow Point. Between February and June 2022, a grader was used to construct more than 60 U-shaped earth banks, measuring 500mm high and 2m across at the bottom. These areas were paired with various treatments such as liquid vermicast foliar spray, solid vermicast and biochar. |

Greenhouse gases and carbon accounting

As part of the RLS project, the Mosely family (Etiwanda) and the Whyte family (Wyndham Station) worked with Dr Jessica Rigg from Select Carbon to understand their farm emissions and create a ‘farm carbon account’.

“A farm carbon account is useful to benchmark and understand your farm emissions, by accounting for sources and sinks of greenhouse gases within a farm business,” Jessica explained.

“If you know where you are starting from you can determine strategies to reduce emissions and identify opportunities to store more carbon in soil or trees. You can’t manage what you don’t measure.”

The Mosely family said the exercise had highlighted the potential of their soil to not only offset emissions to achieve carbon neutrality, but to achieve a net positive position by increasing carbon in the soil.

“We have found great value in working alongside Select Carbon to create a whole farm carbon account as this has allowed us to benchmark where we currently sit in terms of whole farm emissions,” they said.

“Going one step further, the exercise has highlighted the potential of our soil to not only offset emissions to achieve carbon neutrality but increase soil carbon to potentially achieve a net positive position.

“We’re excited to be taking the steps to increase our business resilience and performance, with carbon being a key indicator.”

The carbon accounts were created using the Greenhouse Accounting Framework (GAF) tools developed by the University of Melbourne and the Primary Industries for Climate Challenges Centre (PICCC).

Understanding the numbers

The Etiwanda enterprise includes cattle, sheep and goats, while Wyndham Station includes cattle, sheep and wool enterprises. Etiwanda and Wyndham have average annual rainfalls of 390mm and 290mm, respectively.

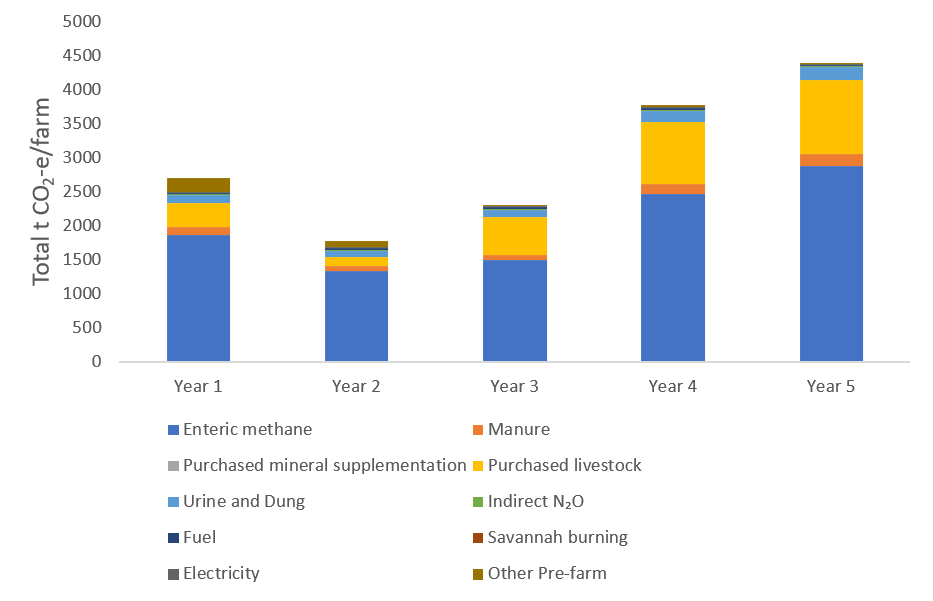

The average annual net farm emissions for Etiwanda were 2,233 tonnes CO2-e/farm (0.13 t CO2-e/ha).

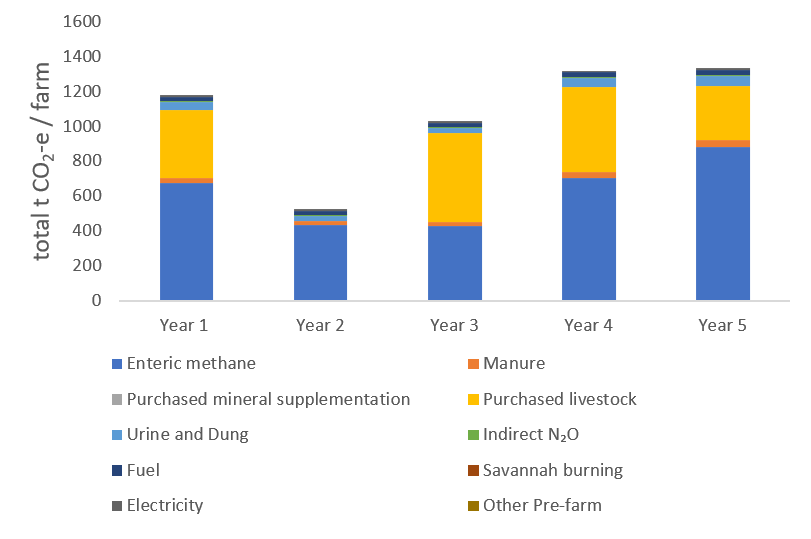

The average annual net farm emissions for Wyndham Station were 1,078 t CO2-e/farm (0.011 t CO2-e/ha).

Average emissions varied across the five years assessed – 2018 to 2023 – and, not surprisingly, methane from livestock was the largest source of emissions for both enterprises.

Figure 1: Annual net farm emissions (total t CO2-e/farm) for Etiwanda. Total emissions are the sum of all livestock enterprises on Etiwanda including sheep and beef (SB-GAF) and goat (Go-GAF). The assessment was made over five production years, from June 2018 to May 2023. Electricity, fuel and diesel were apportioned to each enterprise (therefore, not double counted). The category ‘Other Pre-farm’ includes fertiliser, purchased feed, herbicides and pesticides, lime and livestock away on agistment.

Figure 2: Annual net farm emissions (total t CO2-e/farm) for Wyndham Station. Total emissions are the sum of all livestock enterprises on Wyndham Station including sheep and beef (SB-GAF). The assessment was made over five financial years, from July 2017 to June 2022. Electricity, fuel and diesel were apportioned to each enterprise (therefore, not double counted). The category ‘Other Pre-farm’ includes fertiliser, purchased feed, herbicides and pesticides, lime and livestock away on agistment.

Emissions intensity, in other words the amount of CO2-e per kilogram of product, was calculated for each property and each commodity (Tables 1 and 2). Emissions intensity varied over the five-year period and varied by farm enterprise.

|

Enterprise |

Emissions intensity (kg CO2-e/kg LW) |

||||

|

Year 1 |

Year 2 |

Year 3 |

Year 4 |

Year 5 |

|

|

Beef |

10.6 |

9.0 |

- |

29.2 |

15.8 |

|

Sheep |

49.2 |

15.6 |

16.0 |

15.4 |

13.3 |

|

Goat |

5.8 |

45.5 |

25.2 |

27.5 |

6.73 |

Table 1: Emissions intensity (kg CO2-e/kg live weight (LW)) for beef, sheep and goat enterprises for Etiwanda for the five-year period. The year 3 result for beef emissions intensity was artifically high (and therefore data not shown).

|

Enterprise |

Emissions intensity (kg CO2-e/kg LW) |

||||

|

Year 1 |

Year 2 |

Year 3 |

Year 4 |

Year 5 |

|

|

Beef |

24.5 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Sheep meat |

8.0 |

9.1 |

30.6 |

10.9 |

17.2 |

|

Wool |

25.9 |

28.9 |

95.1 |

34.7 |

53.4 |

Table 2: Emissions intensity (kg CO2-e/kg live weight (LW)) for beef, sheep and wool enterprises on Wyndham Station for the five-year period. Beef emission intensity could not be calculated for years where there were no sales or purchases (years 2 to 4).

Emissions reduction opportunities

“While only carbon sequestration in planted trees is included when using the PICCC GAF tools, carbon sequestration in regenerating vegetation and soil are both important and relevant considerations in whole property carbon accounts,” Jessica said.

“Soil is an important and large store of carbon in the landscape. There are well known benefits of increasing soil organic carbon for agricultural productivity and landscape function. There is also evidence of the role of grazing management and rehydration techniques in building and retaining soil carbon in the rangelands.”

Research has estimated a carbon sequestration rate of 0.17 t C/ha/year in the 0–30cm soil layer (over 20 years) in the Western Division of NSW, if a relative increase of 10% groundcover can be achieved.1

“In the rangelands, well-managed grazing animals are important tools in the landscape to build soil organic matter – the first step in accumulating SOC – by stimulating plant growth, influencing plant composition, ground cover and nutrient redistribution, and breaking down vegetation and litter through trampling,” Jessica said.

“Using Etiwanda as an example, even a conservative increase in soil carbon sequestration (e.g. 0.53% to 0.58% over 100cm over a 25-year period) could potentially offset their average annual emissions [2,233 tonnes CO2-e].

“This demonstrates the potential to sequester more CO2-e than is emitted each year by the farm business. It must be noted, however, that soil carbon sequestration is not currently included in the SB-GAF accounting methodology.”

Where to from here?

For producers interested in developing a carbon account, below are some possible benefits:

- to understand your current position, where emissions are coming from and what levers you could pull to influence your carbon footprint

- to improve future market access, and improve social licence and continued market support for red meat

- to have records or data to voluntarily provide to your supply chain partners

- to access green finance (i.e. sustainable finance).