Playing to win against cattle ticks

03 September 2021

As footy finals season approaches and we stop to watch the high-stakes games on the field, another decades-old game is playing out across northern Australia – cattle versus ticks.

Cattle ticks suck blood, slow growth and production, transmit tick fever, cause hide damage and can ultimately lead to death. So how can northern producers play to win against ticks?

Parasitologist and Managing Director of Dawbuts, Matt Playford, shares his top tips for tick season.

Preparation is key

You don’t win a game if you don’t put in the work beforehand. To get on the front foot, Matt recommends:

- gaining an understanding of the tick lifecycle and biology

- early strategic treatments to stop tick numbers exploding

- later tactical treatments to stop animal health risks and limit pasture contamination.

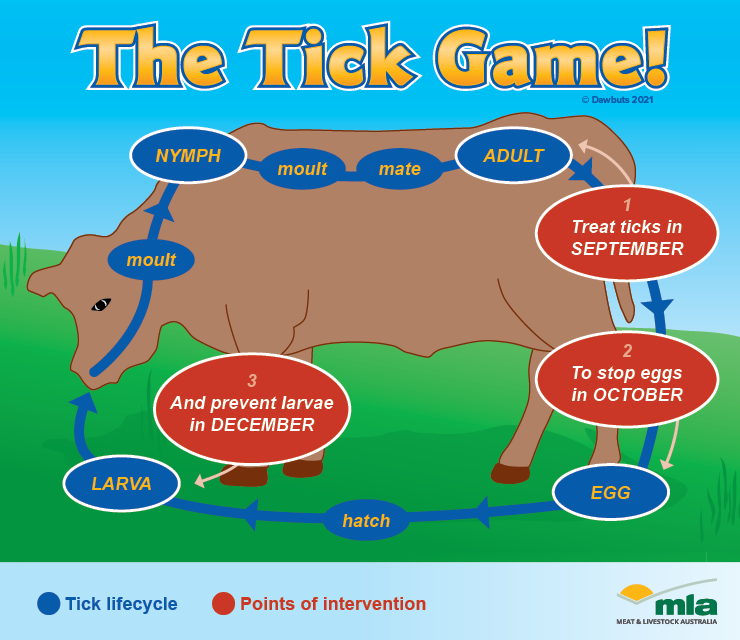

Understanding the tick lifecycle and biology

Australian cattle ticks (Rhipicephalus australis) spend their lives either on cattle (about 3 weeks) or on pasture (minimum 3 weeks, see diagram below). They start off as eggs, which develop on the ground and hatch. The larvae then crawl up the grass and wait for a beast to jump on to.

Once on the cattle, ticks feed, moult, feed, moult again and then mate. For female ticks, pregnancy is the signal for her to begin feeding – not just for herself, but for her babies. The ticks suck more blood over the next few days than over their entire lives to date. The blood they suck is quickly converted into thousands of ripe tick eggs. This results in the big, round female ticks that we see clinging like fat peas to the skin of cattle.

Each tick that engorges takes away 0.6–0.9g of growth from the beast. Once they’ve engorged, the female ticks drop onto the ground and start to lay the eggs.

This means that in winter, particularly in southern inland regions where frosts occur, there aren’t many ticks on the cattle – but there are a lot eggs and larvae on the ground, waiting for warm weather to hatch, develop and crawl onto the cattle.

Once the weather warms up, successive waves of ticks infest cattle, mate, fall off and lay eggs. This is known as ‘the spring rise’ and is particularly seen in Bos taurus herds. A pair of ticks clambering aboard cattle in early September can have as many as 3,000 babies by mid-October. When these offspring infest new cattle and reproduce, their numbers go ballistic.

Early strategic treatments to stop tick numbers exploding

Treating cattle at three-week intervals (short-acting treatments) from the beginning of September breaks the waves of tick reproduction and stops the larvae infesting the paddocks for other cattle. Refer to Table 1 below for types of treatments to use.

Table 1: Types of tick treatments to use in September to suppress the ‘spring rise’ in tick numbers

|

Type of treatment |

Chemicals |

Effective period |

Treatment interval |

Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Short-acting dips, sprays, pour-ons |

Amitrazâ Organophosphatesâ Synthetic pyrethroidsâ Pour on mectins |

18–21 days |

21 days |

Check product label for meat and milk withholding periods, export slaughter interval and re-treatment intervals |

|

Medium-acting |

Injectable mectins e.g. doramectin injectable |

28–30 days |

28 days |

|

|

Medium-long-acting |

Fluazuronâ (best used with a knockdown) |

42 days |

42 days |

|

|

Long-acting |

Long-acting injectable moxidectin |

56 days |

56 days |

* Resistance to these chemicals is widespread – consult local authorities for regional resistance status and submit ticks for resistance testing to find out the best chemical choice for your herd.

Later tactical treatments to stop animal health risks and limit pasture contamination

Treatments with a ‘knock-down’ chemical should be planned for when tick numbers reach the critical threshold numbers for your herd. This is especially important for susceptible cattle such as calves, bulls and Bos taurus herds, including crossbred animals.

A final treatment in autumn will tidy up any ticks on your cattle that could lay eggs that will survive through the next winter. Over several years, the number of ticks on the pasture will decrease and you’ll notice less ticks on the cattle.

Note that internal parasites are also affected by treatment with some tick products (mectins). Repeated use of these products will lead to selection for resistance in gastrointestinal worms.

|

Three ways to beat ticks

* For Queensland producers – submit ticks to the Queensland Biosecurity lab for tick resistance testing on a regular (semi-annual) basis. |